This paper explores the Innovation Dimension of our Broad Transformational Framework. We’ve already set out the types of changes that we exclude from this framework. The next post will investigate how to work on the Organizational Culture, Purpose and People Dimension, with a similar piece in the works for the Technology Depth Dimension. We then get into the playbook—how firms should use the framework to design their own programs that navigate the Journey of Change.

Most organizations today still make things which they sell to customers. When the customer tires of the thing or the thing breaks down, or a shiny new thing comes along (either from the company or a competitor), the customer is expected to buy a new thing. It’s up to the customer to get the value out of the things. And let’s face it, as customers ourselves, our expectations on value have changed over recent years. We want that value—however we perceive it—delivered faster, cheaper, and more conveniently.[1] We want an engaging experience that, rather than paying up front in the hope of deriving value later; we now only want to pay for value as we consume it.

Indeed, the whole nature of competition has moved on. It’s no longer good enough to have great products.[2] We know that customers “want a ¼ inch hole rather than a drill.”[3] Customers want the outcome of the hole, rather than the goods represented by the drill.[4]

As the purchaser, we want the firms that we buy from to work with us, to understand our specific needs, and then to customize the outcome to those needs; instead of trying to give us some sort cookie-cutter, one-size-fits-all standardized offering. [5]

Customer expectations and competition are not the only things to have moved on—even the measure of success has moved on—it’s gone from Productivity to Value:

- In the product-centric world, we measure productivity and efficiency. Executives could claim success by merely reducing the resources required. In this world, Productivity=Value/Resources.

- In a services-centric world, firms focus on effectiveness and measure ways of delivering more value. That means better outcomes within the constraints of the resources available. Now it’s Value=Outcome/Resources.

The New Transformation Equation

That new equation—Value=Outcome/Resources—represents the core of the transformational opportunity. It puts the firm on a very different value innovation curve (think s-curve). The center of a true business transformation is always a shift in value. Without the value change, it’s merely “better sameness.”

The business transformation program is the vehicle of change from the current business as usual to a new level of value delivery. This is especially challenging since it really revolves around engaging a business and its employees into thinking quite differently; these are the same people that have spent their entire lives thinking products and productivity, climbing the hierarchies that go with the silos they create.

Those enterprises that have moved the goal posts—the competitors that are streaking ahead or have suddenly entered your industry—they’ve cracked the code of delivering more and better value. It all begins by “standing in the shoes” of the customer. For example, consider the situation of Apple in the 1990s on the brink of bankruptcy it sought a come-back strategy. Instead of continuing to repatriate income to stockholders, Steve Jobs refocused the firm on ensuring its products delivered the best experience possible to its customers; delighting them, and along the way, turning them into surrogate salespeople.[6]

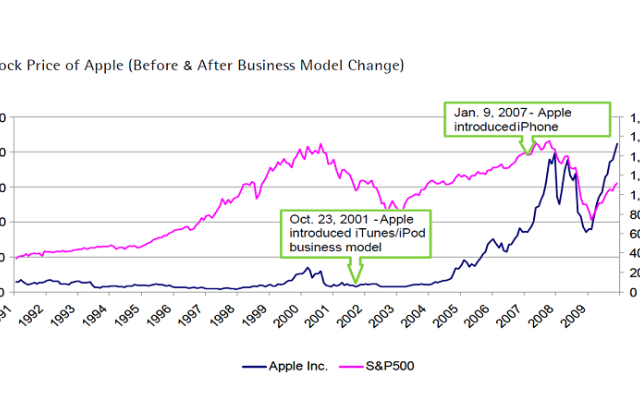

The rest, as they say, is history, but it didn’t happen overnight. Apple not only transformed its own operating model, it progressively transformed the industries within which it chose to operate—the PC business, the music business, and the phone business.

Steve Jobs drove Apple to reinvent its business model and as a result it scaled the heights of success to become the most valuable firm in the world.[7] Apple’s focus on value, in terms of the outcomes it delivered to customers, with close attention to the resources needed, made its business model vastly profitable. Profits came as a result of focusing on and controlling the product experience delivered to its customers; which, in turn, followed on from Apple rediscovering its purpose.[8]

Transformation Means Engaging The Employees At Scale

So how do you get employees to want to change, and collectively reinvent the organization; to innovate and renew the ways in which they engage customer’s and ultimately, modernize organizational business models? This involves engaging your people to:

- Start with the customer. Engage the business to deeply understand customers—their needs, desires and current frustrations. Stand in the shoes of the customer. Move beyond segmentation to build a set of personas—characterizations of customers—and their “jobs to be done.” This helps team’s focus on whose problems they are solving.[9] The transition goes something like this. If an organization sets out to identify customers’ true needs and then improves the experience it delivers by taking out what the customer doesn’t value, then that will almost certainly reduce costs while, at the same time, improving the customer’s perception of the organization and its long-term sustainability. Moreover, as a result of focusing on customers, the organization learns new things about what its customers want or might value, things that it just couldn’t discover anywhere else. The underlying basis for this change is an organizational learning process.[10]

- Rethink the business as a set of “service propositions” outside-in. Map out the customers’ ideal journey, from their point of view (rather than the firm’s point of view). Describe and blueprint the experience that you will provide. Work backwards into the capabilities and processes needed to deliver that experience—i.e. don’t start with your processes that you use today. That route leads to slow incremental change. However, it’s challenging to work backwards from the expectations of customers to design an ideal experience you want to deliver, right back into the processes you need and the role of systems in support of that. We use a “big tent” workshop format to engage multiple teams to co-create their future together. With personas as the focus, teams map out the journey that customers are on as they try to solve for that “job to be done.” Sharing artefacts regularly between the teams, the business people themselves design the experience that they want to deliver as a part of that customer’s journey.[11] Because they work on this together, stealing each other’s ideas, the results are theirs. Business commitment, skin-in-the-game, and ownership of the results are built in because they created the results together. See our short case study.

- Reinvent the business model. That usually means cannibalizing the existing business in one way or another so expect significant resistance. On the other hand, if you have engaged the business effectively to design its own future—the set of service propositions that they want to take to market—protagonists worry less about fixing the past. One of the biggest challenges here it to reimagine the impact of (or potential for) platforms to fundamentally change the rules of competition.[12] While very few businesses have the opportunity to reinvent themselves as multi-sided platform plays—think how the likes of Amazon, Uber, eBay and others were founded as platform businesses—it’s this overall process of engaging colleagues to understand and reframe customer needs that allows firms to innovate. Over time, by focusing on the experience that it delivers—providing better outcomes and more value—the firm distinguishes its offerings from those of its competitors.

Returning to our Apple example, the firm’s meteoric rise took quite a time to gestate as they built the capabilities that would differentiate the firm. The dramatic increase in market cap followed some 5 years after its reorientation around services ecosystem to underpin its product focus—the i-Tunes platform that supported the i-Pod music player (Oct 2001) facilitated a new value delivery curve by enabling the firm to leverage a broad array of app developers for the i-Phone (Jan 2007).[13] By focusing Apple on developing the iPhone as more than just another product, and more than a mere conduit for its own services, Apple changed the rules of competition.[14] It’s not that Nokia did not see the opportunity for an ecosystem—they had a rudimentary ecosystem in place as early as 2000, well before Apple i-Tunes; but they didn’t want to invest in developing the infrastructure to support that ecosystem. Ironically, they were more worried about Microsoft stealing their future. At the time, I was trying to guide them towards a radical expansion of this ecosystem concept. However, the reality was that the culture of Nokia just couldn’t embrace ideas that did not involve the engineering and marketing of a new product; something that they could manufacture at scale.

Conclusion

None of this is particularly new—the ideas have been slowly emerging for years; rather than focusing on products as the unit of exchange, “all businesses are service business.”[15] A service business exists to help customers achieve their goals.[16] Therefore, transformation means refocusing the firm to build compelling outcomes in the form of service offerings, within the constraints of the available resources—i.e. Value=Outcome/Resources.

Transformation based on moving to a new value delivery curve has dramatic implications for strategy. It’s how you get there that’s critical. The key action needed to move past merely improving the current products—another flavor of faux transformation—is engaging employees at scale; that means involving them in the journey, facilitating them as they design new experiences that focus on the customers’ jobs-to-be-done. But that almost certainly means stopping doing some things; dropping some business lines or at least re-focusing the actions of your transformation teams onto a very few things around the business capabilities that matter. Treating the organization as a set of service propositions helps the firm focus on its primary purpose and breaks down the silos that exist in every firm.

Notes:

[1] Value is determined by the beneficiary. “Value is idiosyncratic, experiential, contextual and meaning laden.” Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. (2008). Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 1-10.

[2] According to a recent study by Boston Consulting Group of 30,000 public companies over the last 50 years, “Public companies have a one in three chance of being delisted in the next five years, whether because of bankruptcy, liquidation, M&A, or other causes. That’s six times the delisting rate of companies 40 years ago.” https://www.bcgperspectives.com/content/articles/stratregy-strategic-planning-biology-corporate-survival/

[3] Clayton M. Christensen, Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School refers to the work of Theodore Levitt “Marketers have lost the forest for the trees, focusing too much on creating products for narrow demographic segments rather than satisfying needs. Customers want to “hire” a product to do a job, or, as legendary Harvard Business School marketing professor Theodore Levitt put it, “People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!” This point is that “the job, not the customer, is the fundamental unit of analysis.” http://hbswk.hbs.edu/item/what-customers-want-from-your-products

Others like such as Tony Ulwick have developed “Jobs-To-Be-Done” framework to describe the shift in analysis needed to create a customer-centric organisation. See https://strategyn.com/jobs-to-be-done/

[4] For example, if that hole is needed to extract oil and gas from the ground without spilling any, one might frame the outcome as helping the customer maximise the value of the oilfield without destroying the environment. Clearly, there is no completely standardised way in which oil services operators could achieve this. Yet none of the stakeholders would want an operator to get creative as they strip down a well head. There is always a balance to be struck in terms of how services are composed and the standardisation of components that support them.

[5] “The DuPonts and the Cornings have succeeded not primarily because of their product or research orientation but because they have been thoroughly customer oriented also. It is constant watchfulness for opportunities to apply their technical know-how to the creation of customer-satisfying uses that accounts for their prodigious output of successful new products. Without a very sophisticated eye on the customer, most of their new products might have been wrong, their sales methods useless.” From “Marketing Myopia,” by Theodore Levitt, Harvard Business Review, July 2004.

[6] In 1995, Apple paid a dividend of 4.29c per share. It suspended dividends and focused on value innovation and did not pay a dividend again until 2012, 17 years later. By that time it had split the stock twice and was paying 38c per share in dividend and the stock had gone from around $36 to $700. A single $36 share from 1995 was now worth around $2800 in 2012.

[7] “… Jobs was a master of the leadership process. Time and time again, he gathered intelligence about the future of technology; surveyed the competition and refined his taste; set goals and assembled teams; tracked projects, intervening into even apparently trivial decisions; and followed through, considering the minute details of marketing and retail. Although Jobs had considerable charisma, his real edge was his thoughtful involvement in every step of an unusually expansive leadership process. In an almost quantitative sense, he simply led more than others did.” http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/02/29/our-dangerous-leadership-obsession

[8] Other technology firms have followed in Apple’s footsteps. For example, Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg, in his letter to potential shareholders prior to its 2012 IPO said “Facebook aspires to build the services that give people the power to share and help them once again transform many of our core institutions and industries. … Simply put: we don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services. These days I think more and more people want to use services from companies that believe in something beyond simply maximizing profits. By focusing on our mission and building great services, we believe we will create the most value for our shareholders and partners over the long term—and this in turn will enable us to keep attracting the best people and building more great services.” Facebook exists to help its customers build better outcomes. It makes money as a by-product rather than the primary motivator. Incidentally, it has tripled its share price in four years.

[9] A persona is a rich characterisation of an archetypal customer. Personas are fictional characters created to represent different user/customer types that have similar characteristics. Personas are useful in considering the goals, desires, and limitations of buyers or users in order to help to guide design decisions about a service or product. They can include behaviour patterns, goals, skills, and attitudes, with a few fictitious personal details and a photo to make the persona a realistic character. In B2B scenarios, there are usually multiple personas to consider who have an influence on purchasing and usage decisions.

[10] This aspect is the critical start point for the organisational/cultural dimension. We will cover this more fully in the next post related to the framework.

[11] This is not the same as the customer’s journey through your existing channels and systems. Often that’s the start point for many customer journey mapping exercises.

[12] Marshall W. Van Alstyne, Geoffrey G. Parker and Sangeet Paul Choudary (April 2016) Pipelines, Platforms, and the New Rules of Strategy, Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/04/pipelines-platforms-and-the-new-rules-of-strategy

[13] “Apple conceived the iPhone and its operating system as more than a product or a conduit for services. It imagined them as a way to connect participants in two-sided markets—app developers on one side and app users on the other—generating value for both groups. As the number of participants on each side grew, that value increased—a phenomenon called “network effects,” which is central to platform strategy. By January 2015 the company’s App Store offered 1.4 million apps and had cumulatively generated $25 billion for developers.” Source: ibid

[14] As of March 31st 2016, Apple had a market cap a little over $607B. Today, the number two company by market cap is Alphabet/Google; again they are predominantly a services oriented business, and again based on platform concepts. In the technology industry, Microsoft (#3) once had a strong platform oriented business and IBM (now well down the list) are both busy trying to reinvent themselves as service businesses that leverage powerful technology platforms.

[15] The work of Christensen and Ulwick builds on a widely referenced paper from Stephen Vargo and Robert Lusch in 2004 “Marketing inherited a model of exchange from economics, which had a dominant logic based on the exchange of “goods,” which usually are manufactured output. The dominant logic focused on tangible resources, embedded value, and transactions. Over the past several decades, new perspectives have emerged that have a revised logic focused on intangible resources, the cocreation of value, and relationships. … the new perspectives are converging to form a new dominant logic for marketing, one in which service provision rather than goods is fundamental to economic exchange.” Vargo, S. L., & Lusch, R. F. Evolving To A New Dominant Logic For Marketing. Journal of Marketing, 68, 1–17, (January 2004). Also, see Service-dominant logic: continuing the evolution, Vargo & Lusch, published in the Journal of Academic Marketing Science. (2008) 36:1–10 which is available at https://www.iei.liu.se/fek/frist/722g60/filarkiv-2011/1.256835/VargoLusch-JAMS2008-Continuingtheevolution.pdf

[16] Peter Drucker nailed it in 1954 “The only valid purpose of a firm is to create a customer”.

Article by channel:

Everything you need to know about Digital Transformation

The best articles, news and events direct to your inbox

Read more articles tagged: Featured