The distinction between outputs and outcomes has been an important element of my understanding, articulation and practice of architecting and transforming enterprises. In recent times, I have found that this distinction is not understood or applied in the same manner by other architects and change professionals. This article seeks to:

- outline the features and distinctions between outputs and outcomes

- explore the value and implications of these distinctions

Initial encounter

My first encounter with the distinction between outputs and outcomes was in the context of State Government planning, reporting and accountability, where state government departments developed this mode of reporting in the 1980s and 1990s.

There are many areas of government activity where programs are established to deliver particular “outputs” (services or programs) in the context of achieving broader regional or national outcomes. Examples include:

- Crime prevention, crime investigation and prosecution to achieve community safety

- Public health services to sustain general community health

- Public transport services to ensure affordable community mobility

- Research grant funding to promote innovation and growth

This understanding was further developed through involvement in the developing and implementing strategies for industry development and economic development. Governments cannot create industries and cannot deliver economic growth. Governments can only create an environment in which industries can emerge and flourish, or in which businesses can be established and grow such that more jobs result and economic growth occurs.

In this context, attention might be given to venture capital, commercialisation, support for startups, removal of red tape, provision of advisory services, etc. Each of these provide a specific output, aimed at enabling companies to grow and be more successful, generating more employment opportunities and economic growth.

Relationship between outputs and outcomes

The relationship between outputs and outcomes is many-to-many – one output can have many outcomes and one outcome can be reliant on many outputs. The primary nature of the relationship is reflected in the following statement.

Outcomes arise from the use of outputs

Let’s take an example of a car.

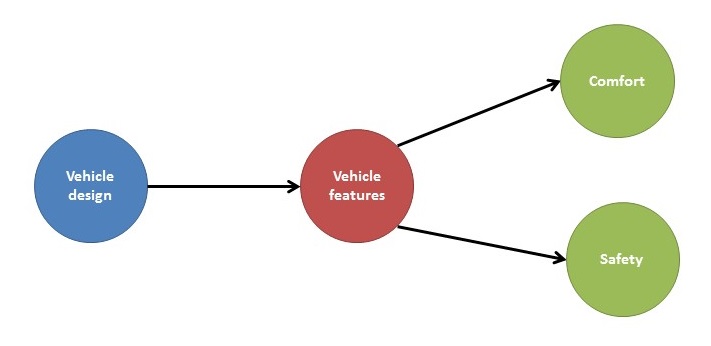

Two outcomes that we might seek in driving a car (the output) are comfort and safety – as shown in the following diagram.

If we consider safety (one of the outcomes), this may be reliant on multiple outputs – the road, the drivers, the car, the traffic – as shown in the following diagram.

The designers and manufacturers of cars give close consideration to the intended use of the car so as to design features which will enhance its use. However, the car designer cannot design all elements of use of the car – some of these are controlled by other entities, including other car designers, the road designer, and the drivers.

If we consider an adverse or unintended event in relation to a car, then there may be multiple factors – car design, road design, road condition, traffic conditions, driver skill and competence. The improvement of use of the car and associated outcomes is not always a matter of improving the design or construction of the car.

Systems view

A systems view assists in exploring and understanding outputs and outcomes. Let’s look at a set of systems-within-systems continuing to use a car as our focus. In this view, we consider:

- An engine as a system

- A car as a system (of which the engine is part)

- A taxi as a system (of which the car is a part and the driver is another part)

- A taxi company as a system (of which the taxi is a part)

In this set of systems:

- the power of the engine (output) is used to move the car (outcome)

- the movement of the car (output) is used by the driver to provide a taxi service (outcome)

- the taxi service (output) is used by the taxi company to provide a responsive taxi service (outcome)

When considering the engine, the car movement is an outcome. The car movement is enabled by the engine. The designer of the engine takes into account the movement that a car will require (eg. pulling a heavy load or accelerating from a standing start) but the designer of the engine is not involved in designing the car and how the engine will be used in the car.

Similarly, the designer of the car takes into account the types of travel that a driver will want to undertake, but will not be involved in designing the use of the car by the driver. The use of an entity may be considered in the design of the entity, but the user designs the use of the entity, not the designer of the entity.

It is common for any system-of-interest to be part of a broader-system, where the use of the output of the system-of-interest, combined with other resources, realises an outcome.

Distinctions and implications

The generic model applied in these scenarios and commonly applied in architectural thinking is shown in the following figure.

The key elements are:

- Systems produce outputs.

- The existence or use of the output generates outcomes

- Customers and stakeholders use outputs which generate outcomes

- In a system-of-systems context, this generates a cascading set of output / outcome relationships.

This aids the processes of designing and architecting by:

- enabling a focus on outcomes to consider different output options which might achieve the same outcome

- prompting consideration of outcome measures which will enable more effective evaluation of the outputs and the processes which produce the outputs

An understanding of outputs and outcomes is valuable, both in an external context, considering customers, consumers and other stakeholders, and in an internal context, where internal output and outcome dynamics also operate. The distinction was invaluable in resetting my perspective on delivery and adoption of IT systems, coming to the realisation that:

- the IT function is responsible for delivering an output – the IT system

- the business functions are responsible for delivering the benefits and outcomes arising from using the IT system

This applies in a similar manner to digital products and services, and digital transformation – where even greater significance attaches to the use of the digital products and services by business functions and by customers and consumers.

It is often assumed that commercial settings entail a simple set of outputs, being the products and/or services provided, and the outcomes being profit and return-on-investment to owners and investors. Closer scrutiny can identify other aspects to the design and operation of an enterprise, considering:

- distinctions between customers and consumers

- broader stakeholders and beneficiaries (regulators and communities)

- balancing owner, customer and employee outcomes

- balancing economic, social and environmental outcomes

This broader set of considerations often requires closer attention in public sector and community sector enterprises.

This is one of a number of articles in the series “Enterprise architecture – digging deeper”.

Other series and articles can be found using the following index.

Article by channel:

Everything you need to know about Digital Transformation

The best articles, news and events direct to your inbox

Read more articles tagged: Featured, Frameworks